Three Spanish Civil War veterans shoot scared rabbits in the 1966 psychological thriller La Caza (The Hunt). They start reminiscing about the war and end up shooting each other.

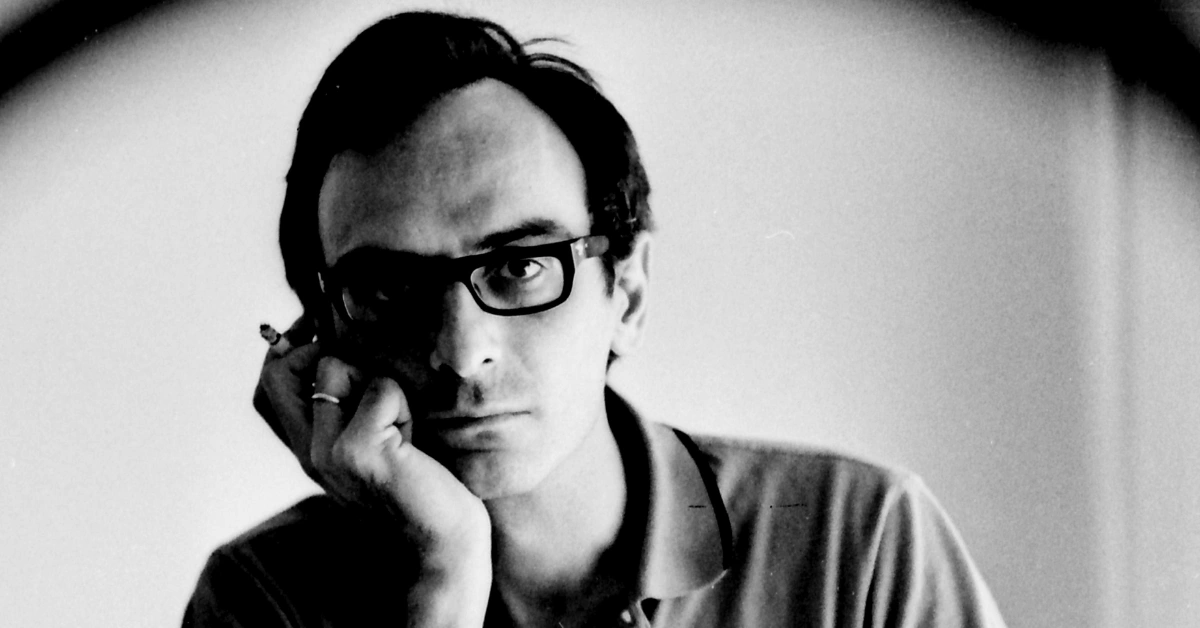

La Caza stirred up a country still haunted by the war and ruled by General Francisco Franco, who had taken power 30 years earlier. La Caza’s 34-year-old writer and director Carlos Saura directly attacked the fascist administration, unlike Juan Antonio Bardem, Luis García Berlana, and Luis Buñuel.

The authorities deleted references to the civil war from the film, a political parable about Franco’s Spain’s simmering tensions.

La Caza won the Silver Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival and made Saura famous. It revived Spanish cinema and shaped it with its politically opportune symbolism for decades.

“I wonder whether, with this constant containment, we are potentially establishing a new language—of silences, symbols,” Saura pondered in 1971. I do it now. I cycle.”

In Peppermint Frappé, a middle-aged doctor gets sexually fascinated with a woman he believes he met in youth, a satire on Franco’s sterility. He received the Silver Bear again a year later.

Saura symbolized Francoist Spain’s cultural dissidence. Right-wing protesters threw stink bombs at Madrid’s La prima Angélica (Cousin Angelica, 1973), a film portraying a man’s civil war experiences. In one scenario, a character’s injured arm is plastered into a fascist salute.

The Information Ministry denied his 1971 script for Anna and the Wolves, in which three brothers seduce and kill a teenage nanny in a rundown mansion.

Saura called the brothers Spain’s three monsters. “Repressed sexuality, religious perversions, and authoritarianism.” Geraldine Chaplin, Saura’s star actress and romantic partner, premiered the film at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival.

After Franco’s death, Saura’s films became less political. He released his psychological thriller Cría Cuervos (Raise Ravens) that year.

The story of an eight-year-old girl who thinks she poisoned her father is based on the Spanish proverb “Raise crows, and they’ll pluck out your eyes,” evoking the complexity and cruelty of parent-child relations.

“Franco took so long to die that we all had time to buy champagne and preserve it in the fridge,” remarked Saura, a chatty man with scraggly hair. “The corks popped when he died. Cría Cuervos didn’t intentionally criticize Francoism. Changing.”

Carlos Saura Atarés, the second of four children of pianist Fermina Atarés and Antonio Saura, was born in Huesca, northeastern Spain, in 1932.

Antonio, his older brother, was an abstract impressionist. His father was a senior tax official for the Ministry of Finance. The family stayed in Madrid during the civil war, experiencing bombing before moving with the Republican administration to Valencia and Barcelona.

This trauma shaped Saura’s films. La prima Angélica immortalized Saura’s friend being hit by flying glass during a bombing, and La Caza recalled his high school’s basement corpses.

After the war, Saura returned to Huesca to live with his grandmother before joining his family in Madrid in 1941, where he became a cinephile.

He studied engineering at Madrid University but grew fascinated with photography, especially ballet and flamenco dancers. His photography was shown at Madrid’s Royal Photographic Society and Cuenca’s city halls in 1951.

His brother persuaded him to leave university and join the Institute de Investigaciones y Experiencias Cinematográficas (IIEC).

He made short films inspired by Antonioni, Visconti, and Fellini’s Italian neo-realist films on memory, fantasy, and dreams. After graduating, he taught until 1964, when his left-wing ideas got him dismissed.

Los Golfos (The Delinquents), Saura’s 1960 debut film, depicted Madrid bullring youngsters trying to escape. The picture was delayed by censors, who cut lines like “it is impossible here to be someone.” Still, it launched the Spanish New Wave, which rejected the nationalistic historical narratives of the 1950s.

Saura left the movement. “I don’t believe in cinema schools,” he stated. “I wanted to depict life, Spanish reality, and Spanish society.”

Saura knew Buñuel at Cannes two years before Los Golfos was exhibited in Spain. Decades later, he made the older director the protagonist of Bunuel and King Solomon’s Table (2001), a fictionalized narrative of his adolescence.

Saura persuaded him to return from exile in Mexico to Spain to make Viridiana (1961), which outraged Franco’s administration with its anticlericalism and stopped Saura’s directing career.

Saura’s societal commentary grew less urgent and less critically appreciated after Franco’s death. Antonieta (1982), about a psychotherapist who studies suicidal women, was his debut international film.

Here are more obituaries articles we’ve published:

- Jacqueline O’Sullivan McDowell Obituary: Studied Spanish At Texas Western University

- Lynda Langford Obituary: Graduated From B.S.C. At Arkansas State University

Blood Wedding (1981), Carmen (1983), and El Amor Brujo (1984) comprised his colorful Flamenco Trilogy (1986). His civil war films continued. He stated flamenco singing was everywhere.

“Soldiers and workers everywhere sang it.” In the 1990s, Ay Carmela!, three Republican traveling players unintentionally enter the rebel area.

He married Adele Medrano in 1957, Mercedes Pérez in 1982, and actress Eulàlia Ramon in 2006. She and his seven children—two sons from his first marriage, Antonio and Carlos; three from his second, Manuel, Adrián, and Diego; a son Shane by Geraldine Chaplin; and a daughter, Anna, from his final marriage—survive him.

The 50-filmmaker said he would sooner die than stop working. In his final week, he released Las Paredes Hablan (Walls Can Speak), a documentary about the roots of art. He died a day before earning the Goya de Honor for “shaping modern Spanish cinema.”

On January 4, 1932, Spanish filmmaker Carlos Saura was born. On February 10, 2023, a 91-year-old died of respiratory issues.

Patricia Gault is a seasoned journalist with years of experience in the industry. She has a passion for uncovering the truth and bringing important stories to light. Patricia has a sharp eye for detail and a talent for making complex issues accessible to a broad audience. Throughout her career, she has demonstrated a commitment to accuracy and impartiality, earning a reputation as a reliable and trusted source of news.