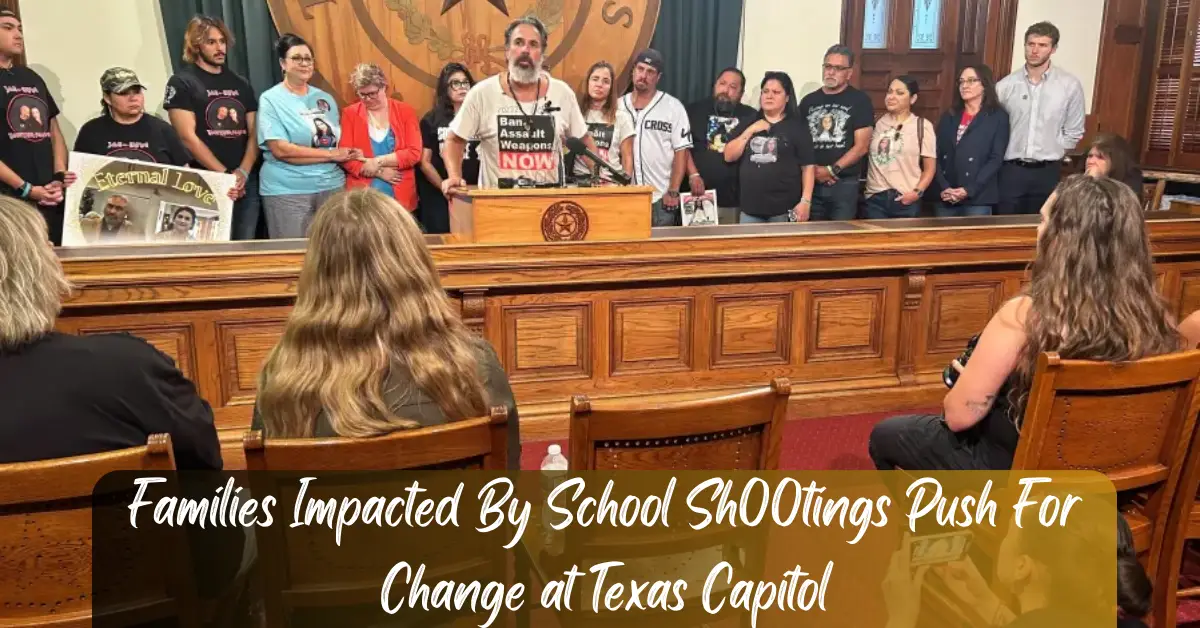

Gun control advocates and families affected by school sh00tings spoke at the Texas Capitol on Monday as part of the Parkland High School Bus Tour in Austin.

The parents of Joaquin “Guac” Oliver, a student d!ed in the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School mass sh00ting in 2018, are driving a bus across the country “to shed light on the dire effects of gun violence across the nation.”

Texas Rep. Vikki Goodwin and families affected by the Robb Elementary School massacre in Uvalde and the 2018 Santa Fe High School sh00ting in Houston joined Manuel and Patricia Oliver.

“Joaquin was shot four times. He suffered. He died slowly,” Manuel, his father, said. “And that was not enough for the whole nation to learn the lesson. Shame on us.”

As part of their bus trip, the Olivers will visit more than 20 places affected by gun violence.

If you’re interested in reading about the recent news, you can check out the below links:-

- Father of Parkland Sh00ting Victim Recount Visiting School Site: ‘It looked like a war zone’

- Painful Memories Resurface As Parkland Parents Revisit Tragic Location

“I am sad that we need to do this, but this is our duty today,” Patricia Oliver remarked. “There’s nothing we can do to bring Joaquin back, but at least we can do a lot to bring awareness of gun violence.”

The Texas Coalition to End Gun Violence also submitted legislative proposals that could prevent future mass sh00tings.

A Tweet posted by the official account of Texas Tribune. You can also find out more information about Families Impacted By School Sh00tings Push For Change at Texas Capitol by reading below tweet:-

8/ During this year’s legislative session, families of Uvalde shooting victims advocated for a bill that would raise the age to legally purchase semi-automatic rifles from 18 to 21.

Many packed into the Texas Capitol, testifying during late-night meetings.https://t.co/Szvz9HxhWo

— Texas Tribune (@TexasTribune) May 24, 2023

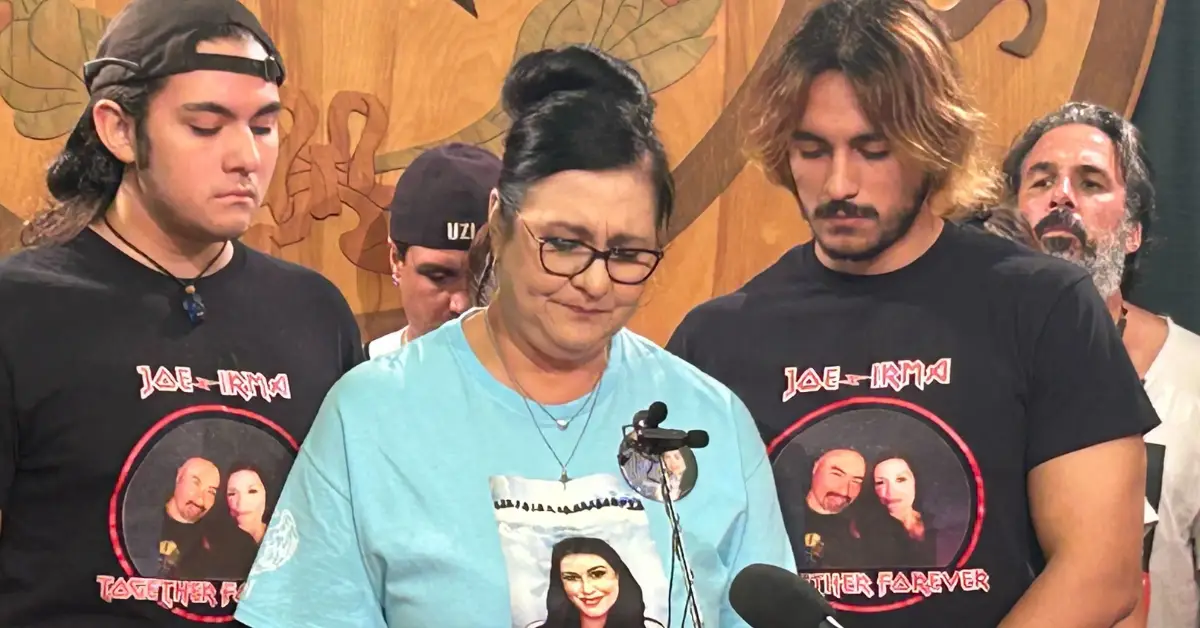

“We don’t want to take your precious guns away. We just want common sense gun laws that will stop this senseless killing,” said Velma Duran, whose sister, Irma Garcia, was ki!!ed in Uvalde.

Till Then, keep yourself updated with all the latest news from our website blhsnews.com.

Tyler is a passionate journalist with a keen eye for detail and a deep love for uncovering the truth. With years of experience covering a wide range of topics, Tyler has a proven track record of delivering insightful and thought-provoking articles to readers everywhere. Whether it’s breaking news, in-depth investigations, or behind-the-scenes looks at the world of politics and entertainment, Tyler has a unique ability to bring a story to life and make it relevant to audiences everywhere. When he’s not writing, you can find Tyler exploring new cultures, trying new foods, and soaking up the beauty of the world around him.